Why Good Projects Still Fail When They Get Big

- Kenneth Linnebjerg

- Jan 22

- 5 min read

Large transformations rarely fail because organizations lack competence, effort, or intent. On the contrary, they are often staffed with highly experienced professionals, supported by mature delivery frameworks, and overseen by serious governance structures. From the outside, everything appears to be in place.

Yet despite this, a striking number of transformations stall, degrade into permanent crisis mode, or quietly dissolve without delivering their promised benefits.

This raises an uncomfortable question: If capable people, proven methods, and strong governance are present, why does progress still break down at scale?

... the answer is not found in execution quality. It is structural.

The hidden assumptions behind project-centric thinking

Classical project management frameworks such as PMI and PRINCE2 were designed to solve a very specific class of problems: delivering a defined outcome within agreed constraints of time, cost, and scope. Their strength lies in predictability, control, and accountability.

They assume that:

work can be sufficiently decomposed upfront

dependencies can be planned and sequenced

progress can be measured through milestones and stage gates

deviations can be corrected through escalation and re-planning

In bounded environments with stable interfaces, these assumptions hold reasonably well. But large transformations violate all of them at once.

Transformation initiatives typically involve:

multiple technologies and platforms evolving in parallel

organizational restructuring and role changes

behavioral change and capability building

regulatory, contractual, or labor-related negotiations

ongoing operations that cannot be paused

Under these conditions, planning becomes provisional, scope boundaries blur, and dependencies shift continuously. Yet the default response is rarely to change structure. Instead, organizations attempt to regain control by adding more of the same: more plans, more steering meetings, more reporting, more escalation paths.

This is the first structural failure mode.

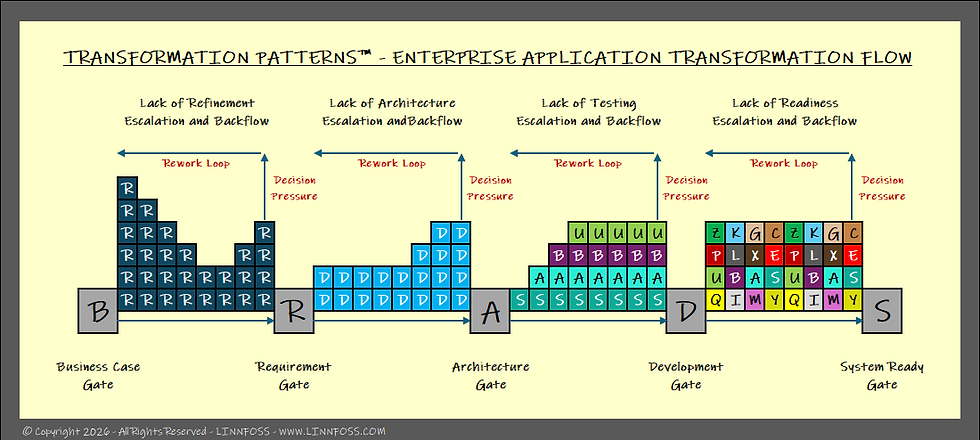

When stage gates become bottlenecks

Stage gates are a cornerstone of traditional governance. They are meant to reduce risk by ensuring that work does not proceed until predefined criteria are met. In transformation contexts, however, stage gates often become bottlenecks rather than safeguards.

There are three reasons for this.

First, stage gates assume that readiness can be assessed conclusively at discrete points in time. In reality, readiness in transformations is partial, uneven, and situational. Some elements are ready early; others lag for structural reasons outside the project’s control.

Second, stage gates concentrate decision authority precisely when uncertainty is still high. This creates a paradox: the more complex the transformation, the more pressure there is to make irreversible decisions with incomplete information.

Third, when stage gates block progress, work rarely stops. It continues informally, bypassing governance. Decisions are made without visibility, alignment, or accountability. What appears to be a compliance problem is actually a structural one: the governance model cannot absorb continuous change.

Escalation is not control — it is a symptom

Escalation is often treated as a safety mechanism. When progress deviates from plan, issues are raised to higher levels of authority for resolution. In theory, this provides clarity and decisiveness.

In practice, escalation in large transformations is usually a signal that the system itself is overloaded.

Escalations multiply because:

decisions span multiple domains with competing priorities

authority is fragmented across business and IT

trade-offs cannot be resolved locally without system-level impact

As escalations accumulate, leadership attention becomes the scarcest resource. Meetings proliferate, decision latency increases, and the organization enters a permanent state of urgency. Ironically, this is often interpreted as a leadership or communication failure, rather than a flaw in how work is structured and handed over.

Escalation, in this sense, is not a solution. It is a pressure release valve for an over-constrained system.

When competence is high but throughput is low

One of the most counterintuitive patterns in transformation work is that highly competent teams can still deliver very little. Individual productivity appears strong, yet system-level progress remains slow and unpredictable.

This phenomenon is described vividly in The Phoenix Project, which reframes delivery problems as flow problems rather than people problems. The book shows how local optimization — keeping everyone busy, maximizing utilization — can actually reduce overall throughput when work is tightly coupled and dependencies are unmanaged.

In transformation programs, this shows up as:

teams waiting on inputs from other teams

work piling up at handover points

rework caused by misaligned assumptions

long feedback loops between intent and outcome

From the outside, this looks like underperformance. From the inside, it feels like constant effort with little progress. The missing element is not motivation or skill, but a coherent model of flow.

Failure as a system property

At scale, failure is rarely caused by a single bad decision or an underperforming team. It emerges from the interaction of many reasonable local choices made within an unsuitable global structure.

Common characteristics of systemic failure include:

work items that are too large to move smoothly

interfaces that are implicit rather than explicit

responsibilities that span too many states of change

governance mechanisms that react rather than regulate

Traditional project management frameworks were never designed to address these properties. They assume that if enough structure is imposed, complexity will yield. Transformation teaches the opposite lesson: structure must be adapted to complexity, not layered on top of it.

.... the problem is not lack of control systems but low, varying quality of work items blocking flow.

Why scaled Agile frameworks don’t close the gap

In response to the limits of classical project management, many organizations have adopted scaled Agile frameworks such as SAFe, or organizational models inspired by Spotify. These approaches have improved transparency, cadence, and local autonomy in many environments.

But despite their popularity, they do not fundamentally address the structural causes described above.

This is not because they are poorly designed. It is because they operate at a different level of abstraction.

Agile methods excel at improving local execution under uncertainty. Short feedback loops, incremental delivery, and cross-functional teams work extremely well - once work is already in a shape and quality that can flow through time-boxes.

At scale, however, Agile frameworks largely assume that:

the shape of work is already appropriate

interfaces between domains are implicitly understood

ambiguity can be absorbed through collaboration

coordination can be managed through cadence and ceremony

When transformations fail under Agile, the response is usually to refine backlogs more, add alignment ceremonies, introduce coordination roles, or extend planning horizons. These measures improve communication, but they do not change the fact that work often enters the system too large, too entangled, or too ambiguous to move safely.

The cost of implicit interfaces

The Spotify model, often cited as a lightweight alternative, deliberately avoids formalizing phase boundaries, entry and exit criteria, or cross-team contracts. This can work well in environments with strong shared culture, high domain maturity, and stable architectural boundaries.

.... in large enterprise transformations, those conditions rarely exist.

Without explicit structure, coordination relies on tacit knowledge and informal negotiation. As scale increases, this becomes fragile. Complexity is not eliminated — it is pushed into human relationships, where it is hardest to see and hardest to govern.

From competence to flow

Reframing transformation failure as a flow problem changes the solution space entirely.

Instead of asking:

who is responsible?

why was the plan wrong?

which meeting failed?

We begin to ask:

how is work shaped before it enters the system?

where does work wait, fragment, or accumulate?

which interfaces introduce ambiguity or rework?

what assumptions are silently carried across handovers?

These questions do not lead to blame or heroics. They lead to design.

Until organizations develop a language for granularity, interfaces, and flow, no amount of competence or framework adoption will be enough. At scale, success is not a matter of trying harder — it is a matter of structuring work so it can move.

Comments